Our top team of Pro Pundits and Hall of Famers write about all things Fantasy Premier League (FPL) throughout the season.

Only Premium Members are able to read every single one of these pieces, so sign up today to get full access not just to the editorial content but all of the other benefits, from hundreds of Opta stats to a transfer planner.

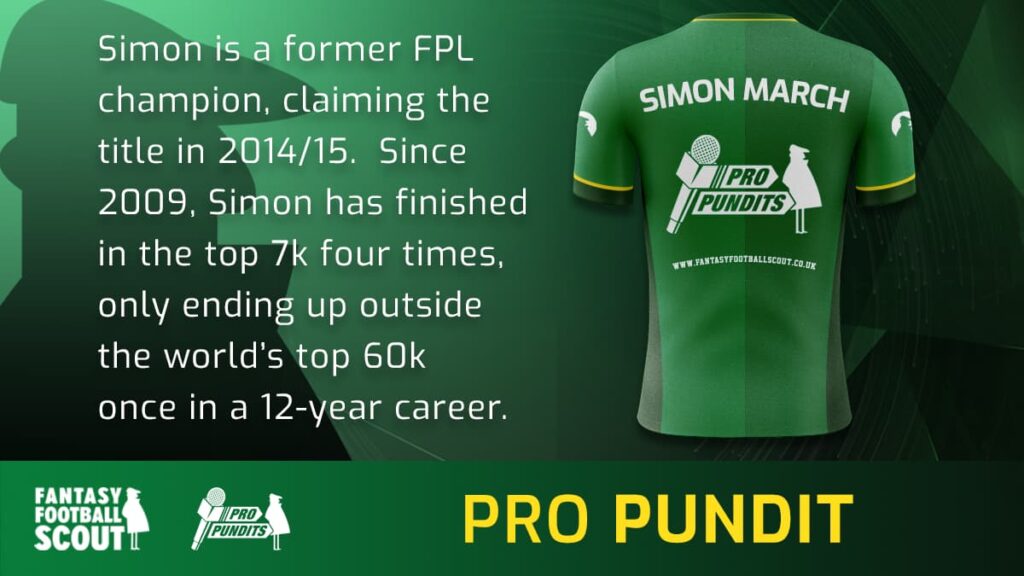

Here, former FPL champion Simon March wonders if we can really define what makes an FPL manager good.

I won’t pretend otherwise: this season has been a real grind. Like every FPL campaign, it’s had its highs and lows, but I personally feel like I’ve had to fight, claw and scrap harder than normal to make any sort of progress this time. In fact, it’s felt like that kind of a game for a few seasons now.

In the three complete seasons from 2019/20 – which we might consider ‘The Covid Era’ of FPL – my ranks have been around 5k, 400k and 48k respectively. With one game left in Gameweek 36, this season I’m currently about 30 points outside of the top 100k, where it feels like I’ve been for a few months. While not impossible, my chances of finishing with at least a five-figure rank (something I’d consider a ‘win’ at this point) seem to be diminishing with each passing Gameweek.

Quite a range but what does any of it mean? Collectively, is it a good performance, a bad performance or a mediocre one? It certainly can’t be called consistent but is consistency even possible when over 11 million managers are playing this game?

I don’t feel like I’ve been playing any differently, so sometimes I question if I still know what it takes to do well at FPL nowadays, or even if I’m any good at it anymore.

What does ‘being good at FPL’ even mean right now? As we head towards the end of this season, it feels like now is a good time to ask.

The good old days

There was a time when ‘being good at FPL’ was very easy to determine; if you finished in the top 10k, then you were good. Then, amongst FPL managers with a lot of top 10k finishes, that question might morph into, “Ah but how many times have you finished in the top 10k” or “Yeah but you’ve never finished in the top 100 though, have you?”. It was a simpler time.

To put into perspective how pervasive the top 10k standard was, I remember appearing very briefly on the very first episode of ‘The FPL Show’ in the year after I won the whole game. When legendary football presenter James Richardson asked where I had finished that year, I was so embarrassed by my rank that I pretended that I couldn’t remember. Would you like to know where I finished? 18k.

The thought of being embarrassed by an 18k rank now seems quite absurd. Maybe it also was back then but, of course, everything is relative. If you finish in the top 7,710,000 this season, you will have beaten twice as many FPL managers as I did when winning in 2015. If you score more than 2,470 points, you’ve totalled more than I did although, in fairness, the chips didn’t exist back then.

Defining ‘good’ evolves as the game grows. Some argue that top 10k is still the benchmark, others say it should be 50k or 100k. The threshold could be even higher if we’re talking in terms relative to what the top 10k previously meant.

But what does it mean if you have a high rank one season and not the next? Can you still be considered good at FPL? While there are a handful of managers who seem to somehow do brilliantly every season, most managers will have at least one ‘bad’ year throughout their FPL career.

This includes all the content creators who you might look to for advice (or entertainment, at least). Over a long enough timeline, even the most freakish of FPL managers – including the Scandinavians – will experience one poor season.

Sadly, off the top of my head, I can name a few who I know in my heart are better at this game than I am but who are currently ranked below me. I might have finished higher than some of them last season, too. However, none of this is enough to convince me that I am now better than them, so if neither past, recent nor current performances are decisive, how do we determine whether we’re good or not?

Is it just luck?

Without getting into another unsolvable debate on this, we all generally agree that luck has something to do with where we end up. Sometimes we have the big dramatic slices of luck that launch us into one direction, such as when our Triple Captain scored 60 points or gets injured 15 minutes into a Double Gameweek.

Yet it’s the little bits of luck that gradually mount up; picking the right player of two with seemingly similar prospects, when your defender gets subbed off on 59 minutes and narrowly misses a clean sheet, getting nine points off your bench thanks to an autosub. These are what make the real difference by the season’s end.

As FPL heads towards 12 million players, it becomes inevitable that the influence of luck will grow even greater and this is exacerbated by there being typically more points sloshing around the game in its current format.

We can use the somewhat popular argument that the last few seasons are ‘asterisk seasons’ anyway, with a succession of unforeseeable events affecting fixture schedules.

These conditions suit some playing styles better than others but, more than anything, they suit those who found themselves on the right side of good fortune. I don’t believe that this makes the game purely just luck but it’s had a bigger influence in these recent campaigns than it might have had in a ‘normal’ one.

Even so, some managers have adapted to these circumstances better than others and we can certainly use adaptability as one trait for a ‘good FPL manager’. After all, sometimes we can help to make luck happen.

Conclusion

Realistically, what determines whether or not you are a good or bad FPL manager must be based on more than just the current season. Consistency of past performances will always be a more reliable indicator than a one-off example. Being defined by your latest season ignores so much context, as is pointing to where you finished ten years ago.

Using the top 10k to define excellence now seems archaic and excessively elitist in a game played by over 11 million people, though I’m sure at least 10,000 FPL managers will disagree with me!

While the skills that generally contribute to being good remain largely the same, the results they yield will become increasingly inconsistent with so many participants. More managers will equal greater variance and, consequently, a higher luck factor.

Equally, it is unrealistic to expect everyone to approach each season in the same fashion. FPL managers are, of course, real people and life sometimes gets in the way. In some years you may have a lot of time to invest in FPL, some years you may not, some years you may be highly motivated and some years you may not. The context will always matter.

So maybe we have to get used to the idea that being ‘good at FPL’ has become more ephemeral or mercurial than perhaps it once was and, really, there is nothing wrong with that. To use an analogy that we’ll definitely all understand; form comes and goes and it’s not always easy to point to why. Liverpool’s Mohamed Salah (£13.1m) is one of the best players the Premier League has ever seen but he doesn’t become a bad player every time he goes a few weeks without scoring a goal.

All we can do is lace up our figurative boots and try our best each season, in whatever circumstances we find ourselves in. Perhaps we should not worry so much about what a good or bad rank is. While there is nothing wrong with taking pride in such things, it is probably unhealthy to internalise it too much, to be too self-flagellating or, indeed, too self-congratulatory over where we finish in an FPL season.

It’s easy to forget at times but FPL is a game and games are supposed to be fun. It’s very possible that the managers who are really ‘good at FPL’ are not the ones with the highest or most consistent ranks but are actually just the ones who allow themselves to enjoy it the most.